Thrones, Crowns, and Stones: Africa’s Hidden Masterpieces Underground - Part 4

By the time I reached the final chambers of the African collection, I realized how much this underground museum had shifted me. It wasn’t just a casual stop on a wine tour anymore. It was a reminder that Africa’s art — whether carved in wood, cast in beads, or sculpted in stone — carries a weight that refuses to be ignored.

These were not curiosities. They were regalia of kings, sacred vessels, ancestral figures, and musical instruments once alive with rhythm. Many sat without signs or labels. But their presence still taught lessons about memory, continuity, and power.

1. Yoruba Beaded Crown (Ade) – Nigeria

One of the most dazzling objects is a beaded crown, or Ade, from the Yoruba of Nigeria. Covered in intricate beadwork of blue, red, and green, it brims with life. Birds perch along its sides, and strands of beads would have veiled the king’s face.

In Yoruba thought, the Oba (king) was both ruler and mediator between the human and spiritual worlds. The crown concealed his face to protect ordinary people from his divine aura. The birds symbolized the mystical powers of women — an acknowledgment that political authority must be balanced with feminine spiritual force.

Seeing it here in Sangalhos, you realize Africa’s royal traditions were no less sophisticated than Europe’s crowns and thrones.

2. Zimbabwean Stone Sculptures – Shona Art

Tucked in another chamber are abstract stone figures, some human, some animal, carved from serpentine and springstone. These are part of the modern Shona stone sculpture movement of Zimbabwe, born in the 1960s in the Tengenenge community.

What makes them extraordinary is how they merge old and new. Inspired by Shona spiritual traditions of honoring ancestors and nature, they also speak to a global modern art language. Today, Shona stone sculpture is recognized worldwide, but its heart remains Zimbabwean.

To find them in a Portuguese wine cellar is a surprise. To recognize them as living traditions, still practiced today, is a gift.

3. Luba Maternity Figures – Congo

Several wooden figures depict women with children clinging to their backs or seated with bowls in their hands. These are characteristic of the Luba people of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In Luba society, women held key roles as guardians of spiritual knowledge. Maternity figures symbolized not just fertility, but also continuity of lineage and the wisdom of mothers. Some served as divination tools, others as prestige objects owned by kings and chiefs.

Even stripped of context, their tenderness radiates. The children on their backs, the half-closed eyes, the carved scarification — all speak of women as vessels of strength and continuity.

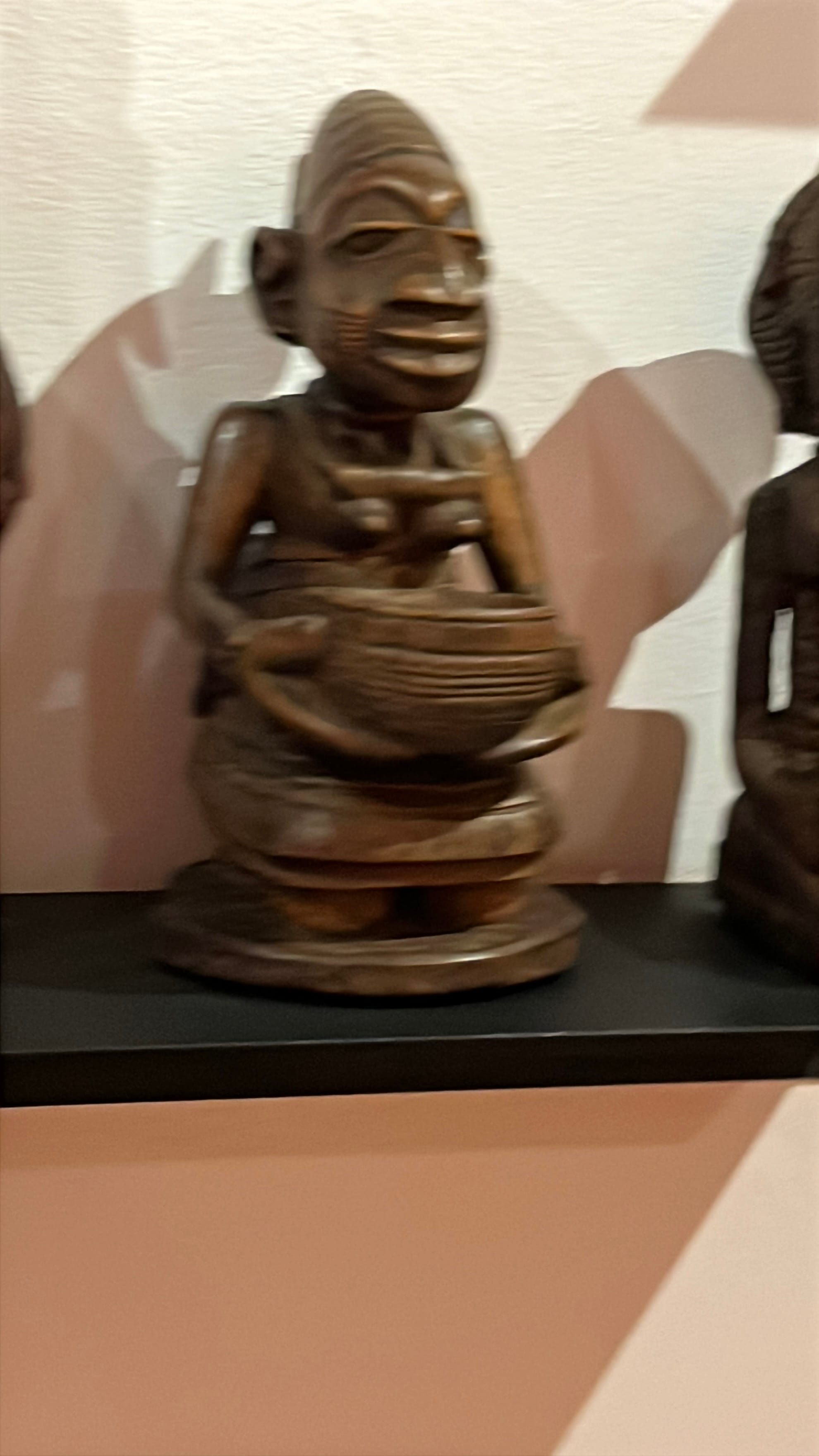

4. Ritual Offering Figures – Yoruba & Luba

In another case sit kneeling figures holding bowls. These are offering vessels, common across Yoruba (Nigeria) and Luba (Congo) cultures.

The bowls once held kola nuts, food offerings, or ritual substances. They embody service — the human offering to the divine, the bridge between the everyday and the sacred.

Today, they sit empty. But the gesture remains. Even in stillness, the figures remind us of generosity and communion.

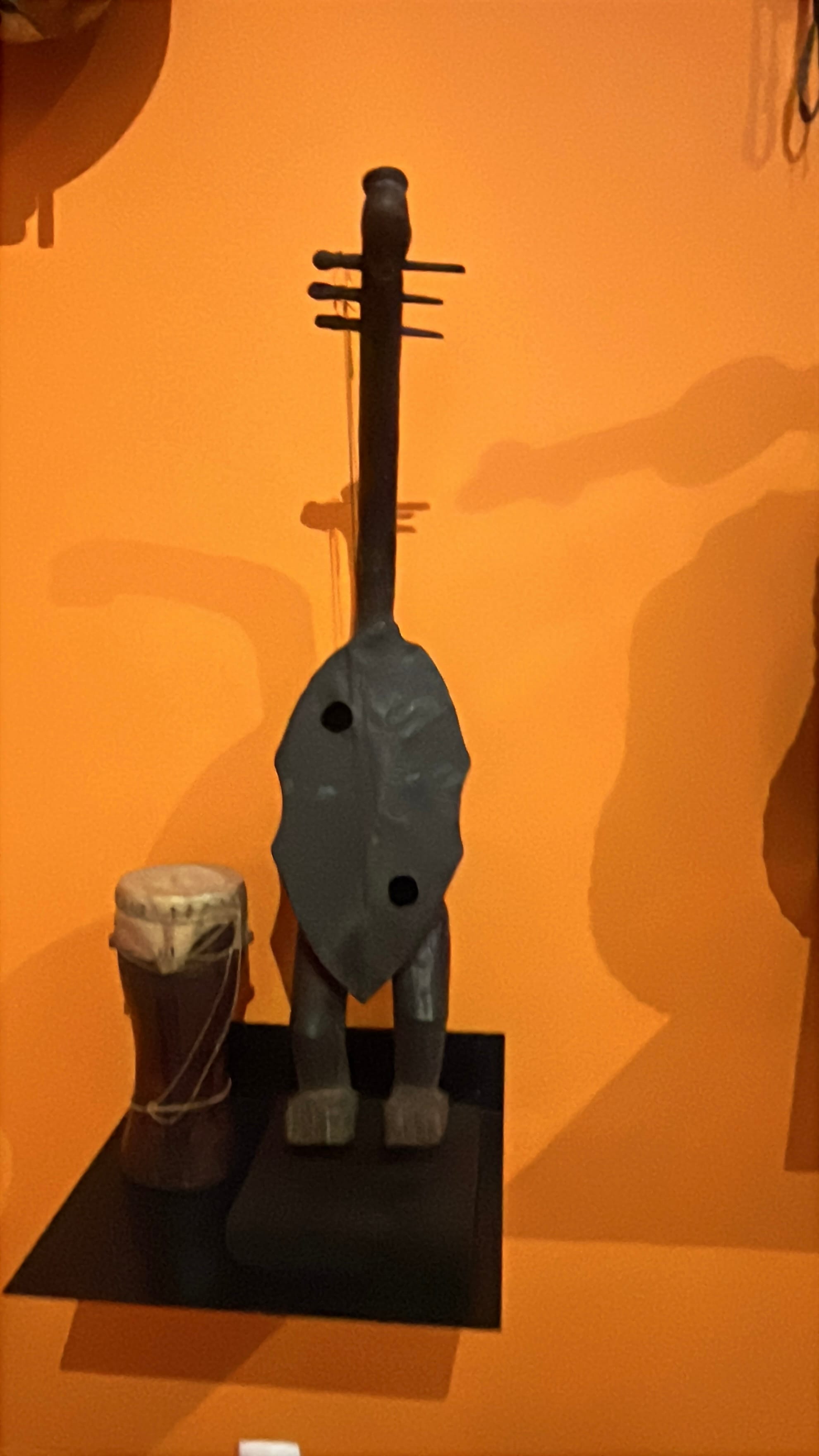

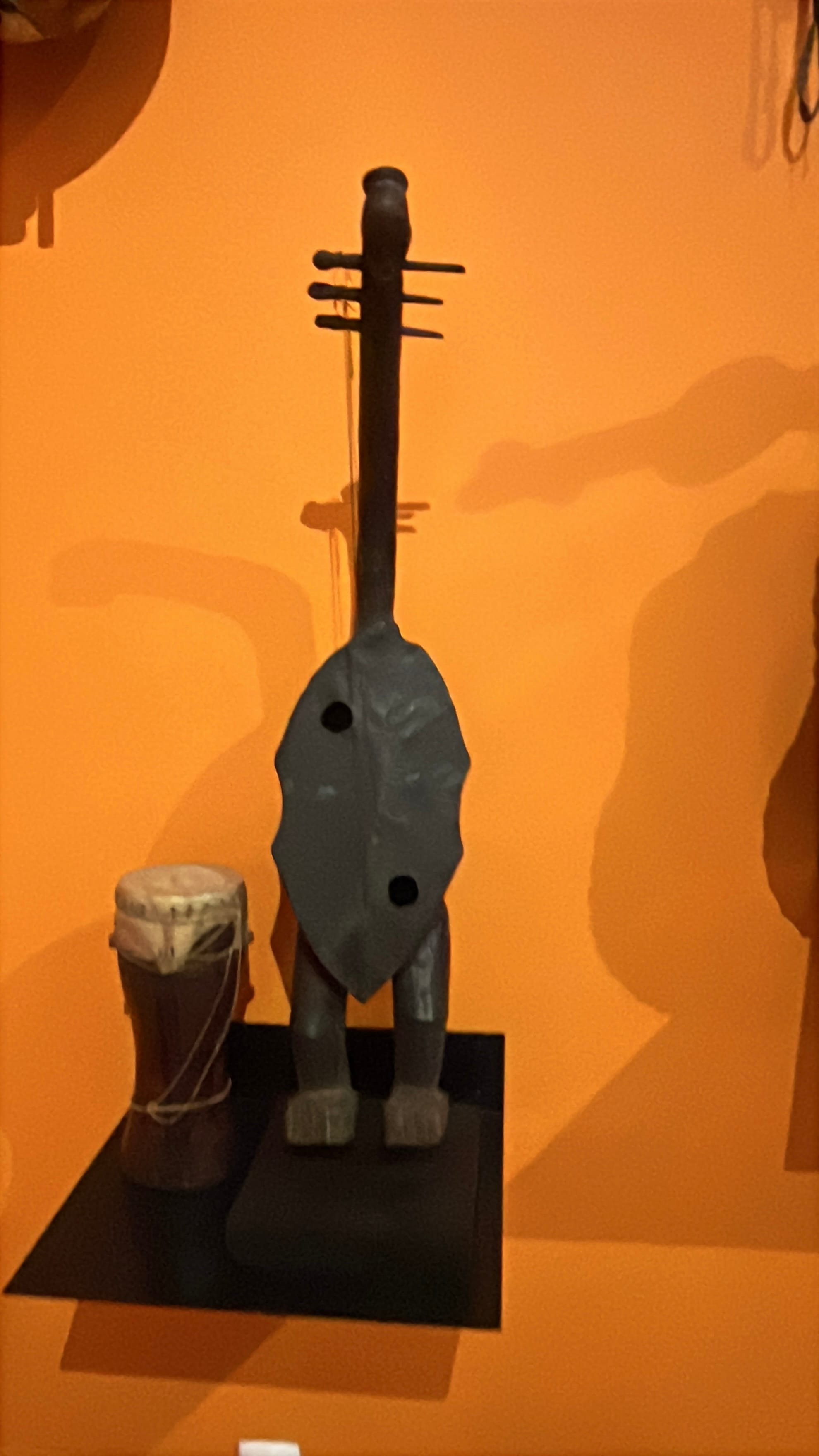

5. Musical Instruments – Drums and Strings

Stacked in corners are drums stretched with animal skin, lutes, and stringed instruments. In Africa, music is never just entertainment. It is language. It is history.

A drumbeat can call a village together, announce a death, or send a message across valleys. A stringed lute can carry a griot’s genealogy, preserving history when no books were written. These instruments in the Aliança museum are silent now — but they once spoke, sang, and guided entire communities.

6. Power Figures with Raffia – Kongo Peoples

Short, round-bodied figures dressed in raffia skirts and feathered headdresses stand like guardians. These are Nkisi figures from the Kongo peoples of Angola and the DRC.

They were vessels of spiritual force, invoked for healing, justice, or protection. Medicines were inserted into their hollowed bellies, activating them. Community members might strike them with nails or blades to “seal” an oath or unleash their power.

In the museum, they are displayed as art. In their original homes, they were instruments of law, healing, and survival.

Walking Out of the Underground

By the time I emerged back into the light of the winery, the air felt different. The wine tour suddenly seemed like a footnote. What lingered was the underground memory of Africa.

From terracotta grave markers in Niger, to Yoruba crowns in Nigeria, to Luba maternity figures in Congo, to Shona stone carvings in Zimbabwe — the collection in Sangalhos is astonishing. It deserves to be seen. It deserves to be studied.

But most importantly, it deserves to be remembered for what it is: not just “art,” but humanity’s heritage.

Member discussion