Spirits in Wood: African Masks and Sculptures Underground - Part 3

The deeper I walked into the African galleries of the Aliança Underground Museum, the more I felt surrounded by eyes. Long noses, bulging foreheads, horns, serene white faces—all carved from wood, all staring back through the dim museum light.

Masks and sculptures are among the most powerful African art forms because they were never meant to sit on walls. They were meant to move. They were meant to be danced, to conceal and reveal, to bring ancestors and spirits into the human world. Seeing them lined along the corridors of a Portuguese wine cellar is both haunting and mesmerizing.

1. Multi-Headed Animal Spirit Mask – Burkina Faso

This snarling, multi-headed mask immediately catches attention. Three animal faces extend outward, jaws open as if mid-roar.

Masks like this come from the Bwa and related peoples of Burkina Faso, used in initiation ceremonies and agricultural rituals. The multiple heads symbolize the untamed power of the bush—forces that must be controlled through community and ritual. In performance, dancers would move fiercely, channeling the spirit world into the village.

Here in Portugal, it stands silent, its energy muted but not gone.

2. Dogon Funeral Masks – Mali

Long vertical wooden masks with narrow faces and towering structures—these belong to the Dogon of Mali.

Dogon masks were carved for the Dama funeral ceremonies, where entire villages danced for days to guide the souls of the dead into the afterlife. Each mask represented a different spirit: hunters, animals, ancestors. The tall, plank-like masks served as bridges between the earth and sky, reminding participants of their place in the cosmic order.

Standing in front of them in the museum, I could almost picture the dust of a Dogon village rising as dozens of masked dancers moved in rhythm, sending spirits on their journey.

3. White-Faced Punu Masks – Gabon

One of the most graceful objects in the collection is the Punu mask from Gabon: painted white with delicate features, almond-shaped eyes, and elaborate hair carved into braids.

These masks represent idealized female ancestors. The white pigment is kaolin, a clay associated with purity and the afterlife. Punu masks were often danced on stilts during festivals, where acrobatic performers would leap and spin high above the crowd, embodying ancestral spirits returning to bless the living.

In Portugal, the stillness robs them of movement, but not of their dignity.

4. Kuba or Bwa Tubular-Eyed Mask – Central Africa

A striking mask with tubular eyes and geometric features seems almost modernist in style. But this is African abstraction at its most ancient.

The Kuba (DRC) and Bwa (Burkina Faso) carved such masks for initiation rites. The exaggerated eyes symbolize spiritual sight—seeing beyond the human into the supernatural. These masks weren’t designed for portraiture; they were designed for transformation.

Looking at it underground, I thought of how many European artists—Picasso, Braque, Modigliani—borrowed heavily from such African forms while rarely acknowledging their sources.

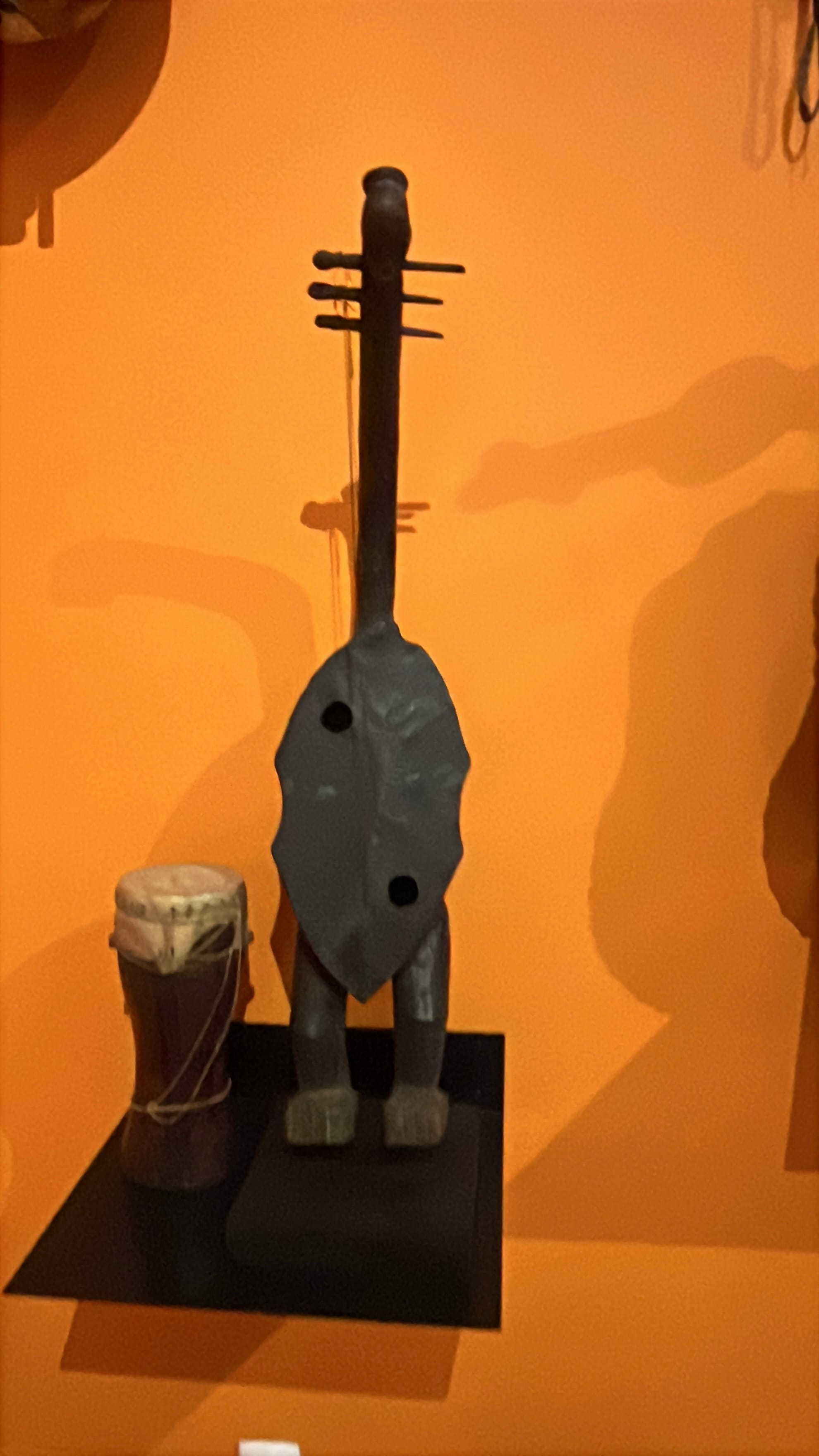

5. Baule & Luba Sculptures – Côte d’Ivoire & DRC

In one corner, I found wooden sculptures: a seated man, a seated woman, and a tall elongated figure.

The Baule of Côte d’Ivoire are famous for their pairs of male and female figures, often representing spirit spouses or idealized ancestors. The Luba of Congo carved elongated figures tied to kingship and divination. Both traditions place great emphasis on balance—male and female, living and ancestral, human and spiritual.

Placed side by side in the museum, they almost feel like a council of elders, holding their secrets close.

6. Nkisi Figures in Raffia – Congo Basin

Two short, round figures draped in raffia skirts and feathers dominate one display. These are Nkisi Nkondi figures from the Kongo peoples of the Congo Basin.

They are not decorative. They were power objects, activated by healers and diviners with medicines inserted into their hollowed bellies. The raffia skirts and feather headdresses mark them as vessels of spiritual authority.

In their original villages, they would have been invoked for justice, protection, or healing. Here, they look fierce even in silence, like guards placed at the threshold of memory.

Walking Among Spirits

As I wandered through this underground chamber, I realized that what moved me wasn’t just the artistry, but the absence of sound. These masks and sculptures were carved to be seen in motion, with drumbeats and chanting. Here, they were silent.

And yet, they still radiate presence. You can almost feel the weight of their history pressing through the walls: ancestors remembered, spirits invoked, contracts sworn, kings crowned.

For travelers, this is not just a wine museum with curiosities. It is an encounter with Africa underground—a reminder that art is never only art. It is memory, spirit, and power.

Member discussion