Ever Wonder What's Beneath the Wine Barrels? I Made a Fabulous Discovery in the Aliança Underground Museum - Part 1

I had a rental car for a few days, so I decided to take out some of my friends on a new discovery. When you drive into Sangalhos, near Aveiro, Portugal, the road signs and landscape are clear: this is wine country. The Aliança Vinhos de Portugal winery welcomes visitors with polished tours, tastings, and barrels stacked like cathedrals all underground. But I wasn’t here just for wine. Many of them, I have had from our local grocery store. I was here for something that almost felt like a rumor: the Aliança Underground Museum.

Walk past the bottles and marketing displays, and head outside to another building. We headed through a huge iron door and towards a stairwell that led down, not so deep at first, but we kept going for what seemed like miles. The air becomes cooler and heavier. Before the endless wine cellars, we stumble upon walls and walls of artifacts. The winery doubles as a museum, housing the private Berardo Collection, which features objects from India, Brazil, Africa, and Europe, all tucked beneath the ground.

I had heard whispers of this place described as a “side show” by one of our Angolan friends. It's like a cultural add-on to sweeten the wine tour, I guess. But the truth is, this collection deserves attention in its own right—especially the African art, the focus of this, and my next three articles.

An Unexpected Encounter with Africa Underground

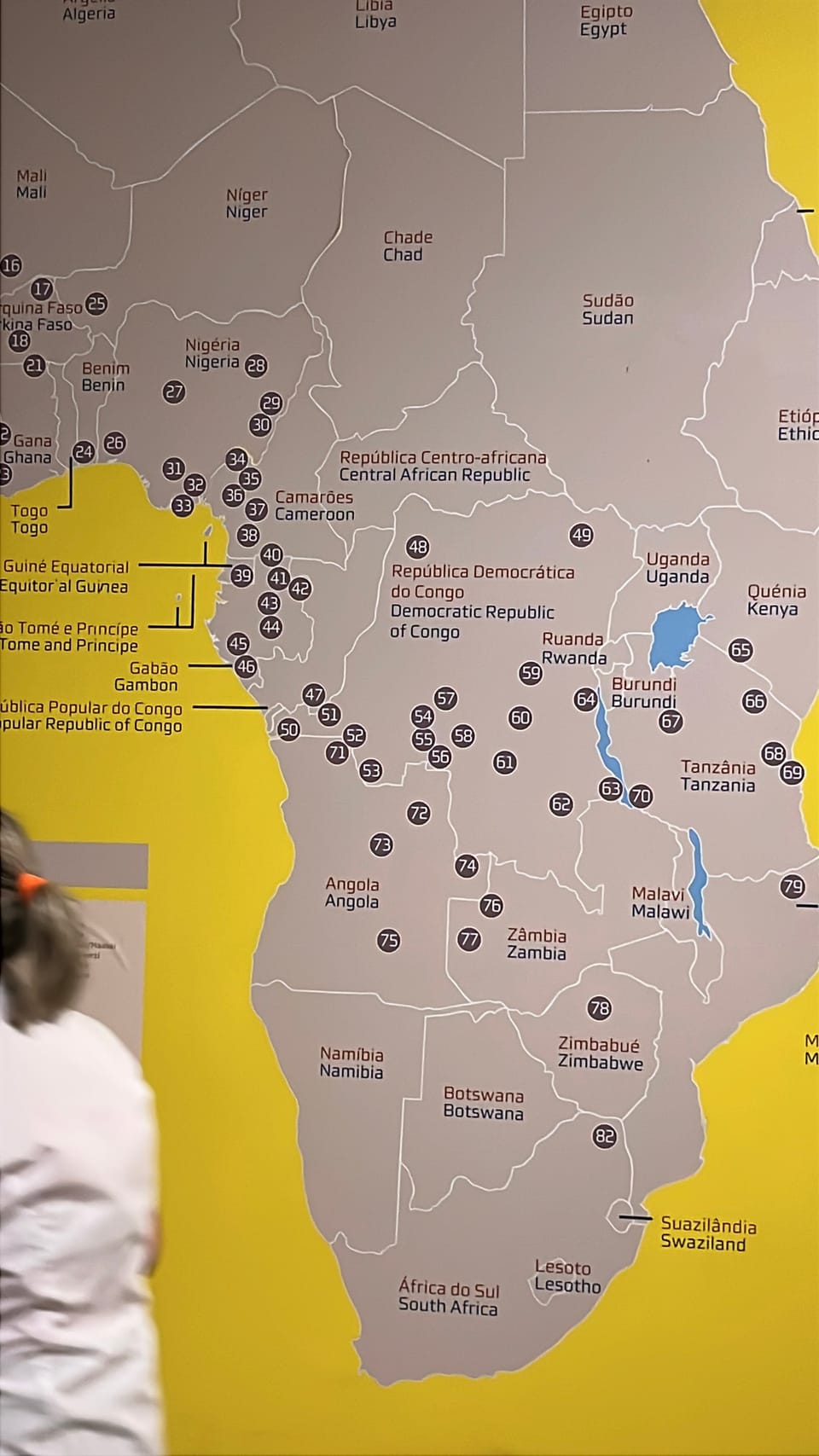

The African section doesn’t shout its presence. There are no big banners, no introductory videos. You turn a corner, the tour guide shows you a map of Africa (see the feature image), and suddenly you’re standing before terracotta monuments from Niger, ivory carvings from the Congo Basin, and walls covered in lots of masks from Gabon, Mali, and Burkina Faso.

The surprise hit me hardest when I realized how much of it was presented without context. Many pieces were unsigned, undated, and unlocated. No notes on which ethnic group made them, which kingdom they came from, or what language their makers spoke. I wondered why their cultural significance was not shown on signs next to them or in videos. Even those QR codes that lead to a website with details would have been helpful. For someone with roots and interest in African history, it felt strange. It was like seeing powerful ancestral spirits presented in silence and without reverence.

The irony isn’t lost. Africa, the cradle of humanity and the source of all civilization, too often has its history displayed in fragments, stripped of its names and identities. And here it was again, not in a capital city museum, but in the basement of a Portuguese winery. When I mention the place to my Portuguese friends, they have never heard of it!

A Private Collection, A Global History.

The Aliança Underground Museum is part of the Berardo Collection, a vast and, I mean vast, private collection assembled by Portuguese businessman José Berardo. His collections span continents and include minerals from Brazil, fossils from South America, ceramics from Portugal, and ethnographic art from Africa and Asia, with a primary focus on India.

In Lisbon, Berardo is best known for the Berardo Collection Museum of Modern Art in Belém. I haven't seen it yet, because I need an entire day to take it all in. But in Sangalhos, his underground trove is something different: eclectic, surprising, and in many ways intimate. It feels less curated for academia and more like a collector’s treasure cave, where items of sacred, functional, and aesthetic value sit side by side.

That intimacy with you as you stroll through the halls is part of what makes the African section powerful. These are not reproductions or casual souvenirs. This is the real deal. They are authentic ritual objects, sculptures, and vessels that once lived in villages, shrines, family homes, communities, religious places, and courts across Africa. And now they rest here, halfway between preservation and obscurity, and God forbid that place should flood.

Why the African Collection Matters

As I walked through, I kept wondering what these objects represented:

- Terracotta figures placed on graves in Niger to guide the dead.

- Ivory carvings passed through hands during ceremonies of lineage and prestige.

- Masks that once danced in fire-lit ceremonies, transforming men into spirits.

- Power figures embedded with nails and mirrors, used to invoke protection or justice.

- Beaded crowns worn only by kings, shimmering with sacred authority.

Together, they form a tapestry of African life: fertility, governance, ancestry, music, war, technology, and philosophy. Yet here, they were scattered across corridors without the connective tissue of a story. I serve on the board of the Museum of Diversity (MoD), and it is with this interest that I know these objects deserve far more reverence and curation.

For the visitor, this silence becomes an opportunity. If you care about Africa—and I believe every human should, since it is humanity’s beginning—this is a place to start asking questions.

Awe and Unease

The experience of the Aliança Underground Museum is both awe-inspiring and unsettling to me. I think it was the same for some of my friends who came with me. Awe, because you’re confronted with works of stunning craftsmanship—stone sculptures from Zimbabwe, maternity figures from the Congo, Yoruba crowns alive with beads. Unsettling, because of how little you’re told about them, and how far they are from home.

How did they get here? Were they purchased, traded, or looted? What communities were left without them? How did they get them into Portugal, and why were they even collected?

No plaques answered these questions. And maybe that’s why this museum lingered in my mind long after I left. It forces you to think not just about the art, but about its journey—and about the imbalance of cultural memory between Europe and Africa.

Why You Should Go

For travelers, this is more than a wine stop. That's the end to cool your souls if you get emotional. It is a portal into African civilizations, hidden underground in a Portuguese town most tourists pass by.

If you’re planning a trip to Aveiro or Porto, make time for Sangalhos along the way. Wander through the underground hills of wine barrels, but don’t stop there. Keep going down, into the vaults. Let the African art confront you. Match the objects with what you know—or use the silence as a spark to learn more when you leave.

Coming Next in This Series

This article is the first in a four-part series that explores the African art at the Aliança Underground Museum. I decided to use AI to conduct research and determine the provenance of each piece. I could be wrong on some of them, so I am relying on readers to send in corrections in the comments or email me directly.

Stay tuned next week for Part 2, where I try to identify some of the pieces.

Member discussion